Making A Crankshaft -10 (Installation)

Yes. As usual, this project has taken at least twice as long as I had planned.

But, the making of the crankshaft has finished, and I have started to install it in the traction engine.

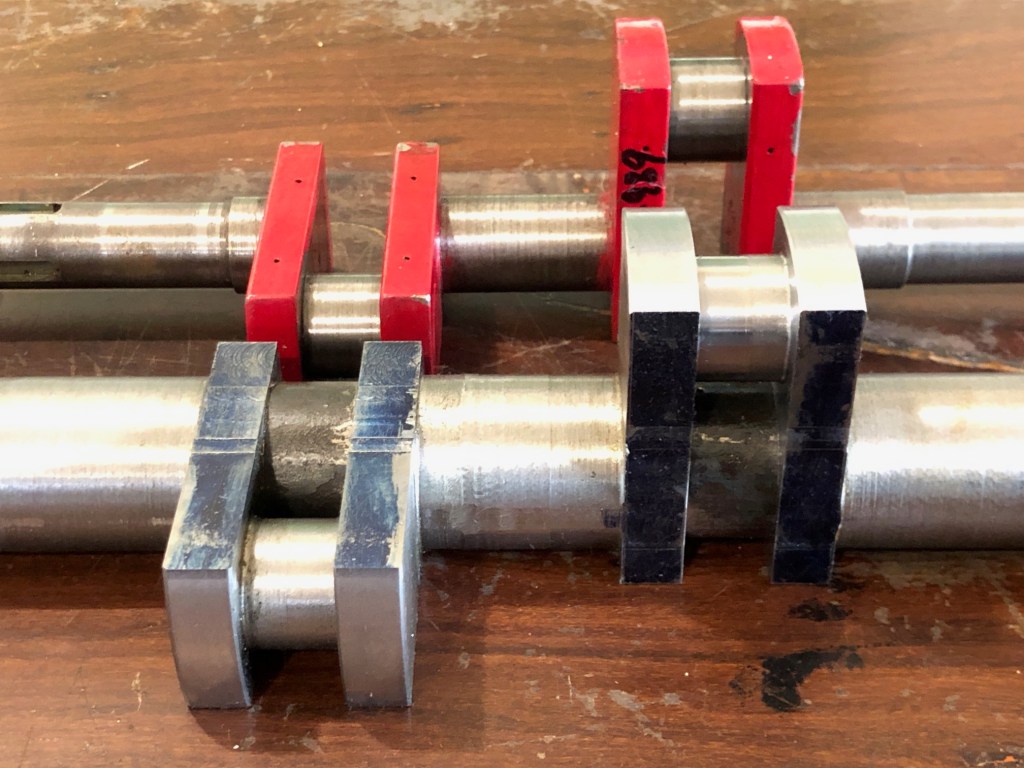

I installed the valve eccentrics, approximately in their correct positions. I had marked the eccentrics according to their position on the old crankshaft. The exact timing positions will be determined when everything is installed.

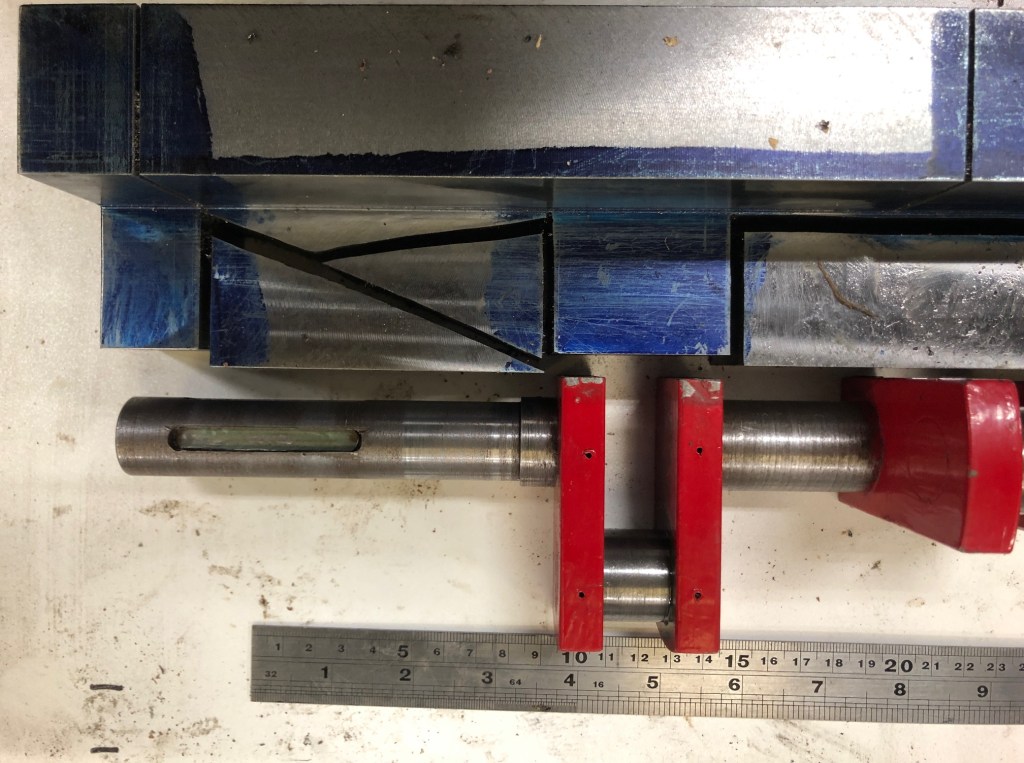

The crankshaft was placed in the main bearings. I had made the crankshaft with the bearing spacings according to the original plans. Then realized that the original maker had varied some of the dimensions, including the distance between main bearings. So I needed to gain approx 2mm between the main bearings. I achieved that by taking some width off one of the gears on the lathe.

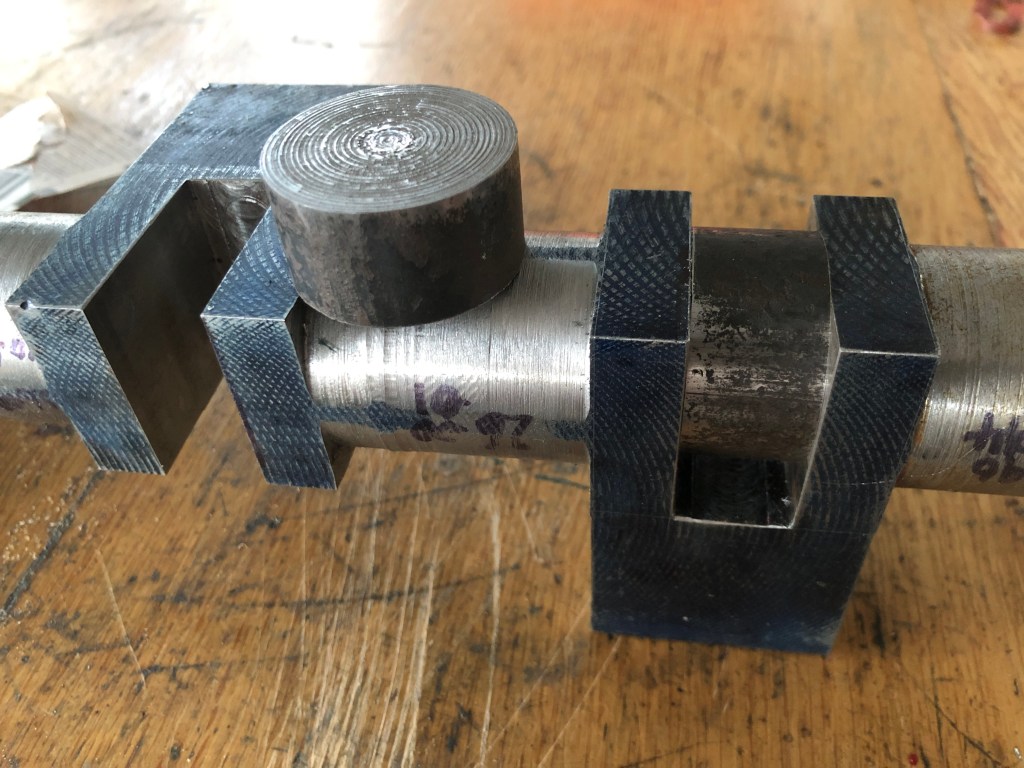

Today, I started to fit the big end bearings. I had deliberately made the big end journals 0.1-0.2mm bigger than the old ones, knowing that I would have to increase the diameter of the big end bearings.

The 3 jaw chuck is holding a smaller independent 4 jaw (because I did not have a suitable backing plate for the small 4 jaw. And I needed a small 4 jaw so the bearing halves would seat on it.). The big end bearing is held in its engine housing, and the original bearing hole was clocked in the 4 jaw as accurately as possible, after tapping it against the jaws with a light hammer. Then the bearing was turned to the slightly larger diameter.

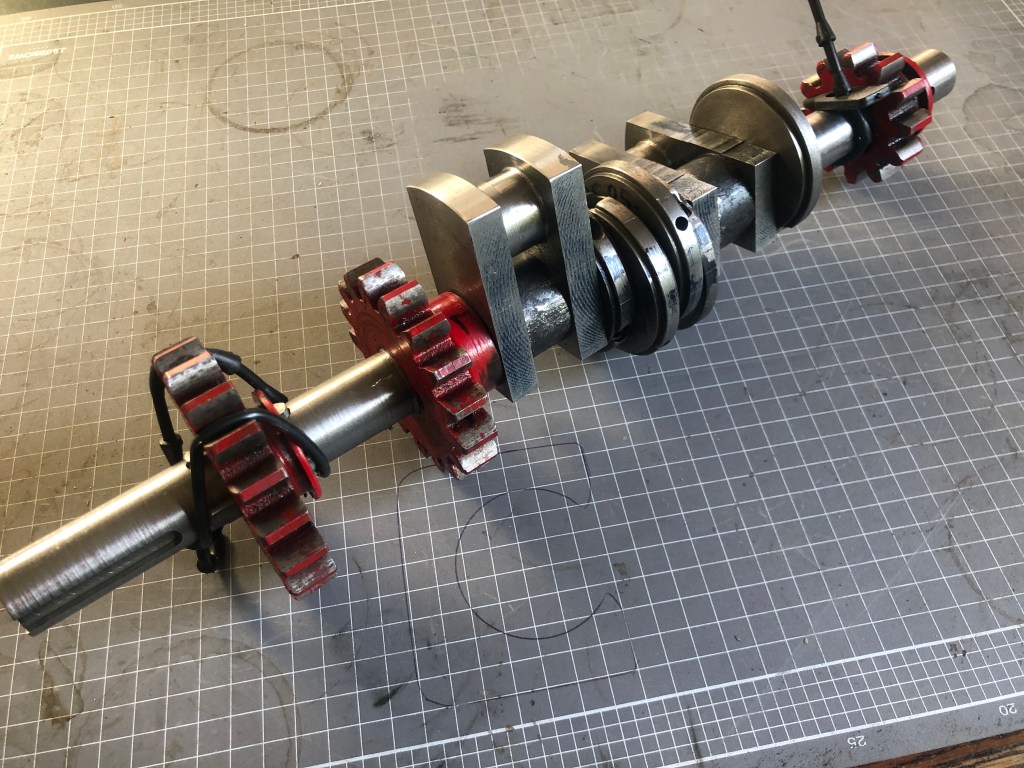

The crankshaft with the main bearings and big end bearings tightened. The eccentric rods are held out of the way with aluminium wire. The shaft turns but it is very tight, and will need further freeing. I have used some “Gumption” but it needs a bit more. Maybe running the engine on compressed air will free it up.

A quick test with the flywheel in position looked promising in terms of run out.