Model Armstrong 110pr Sights

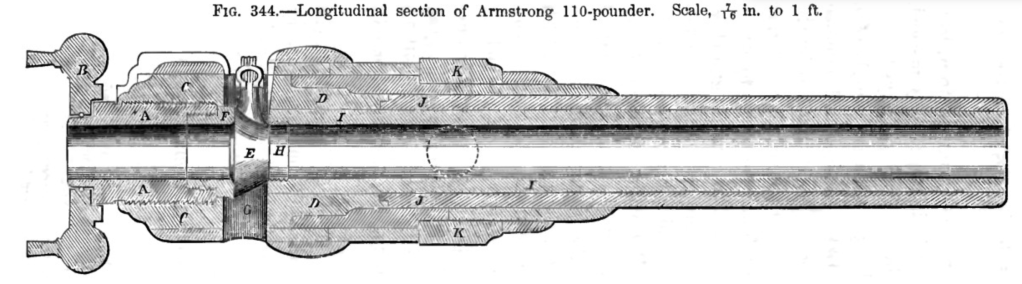

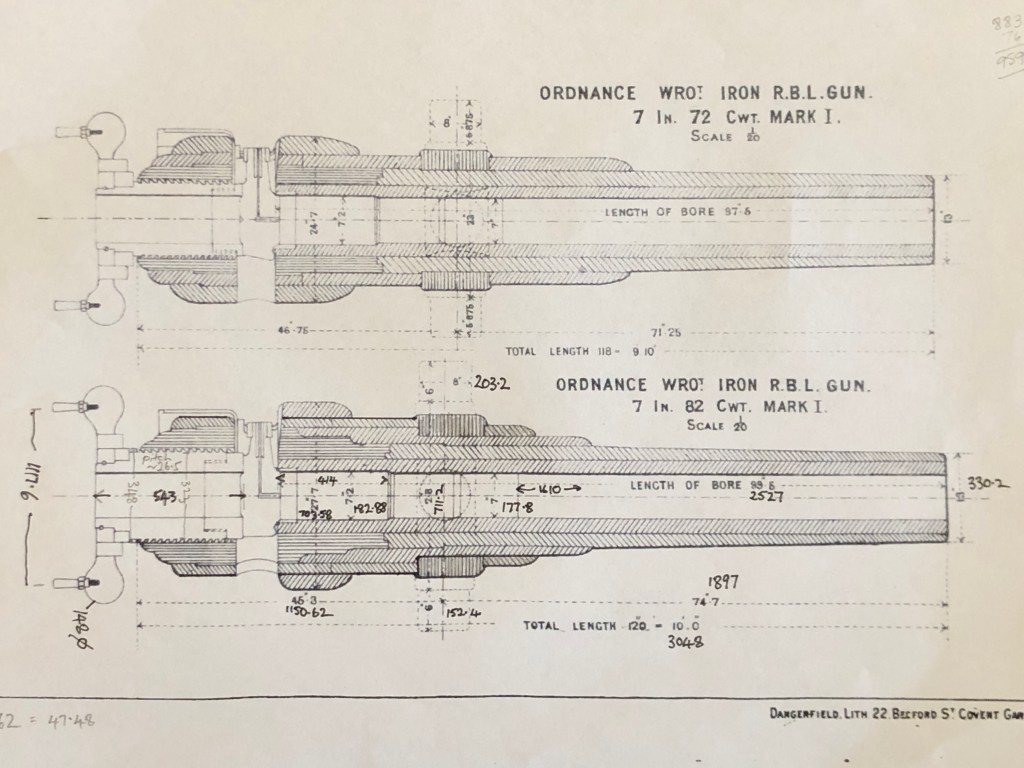

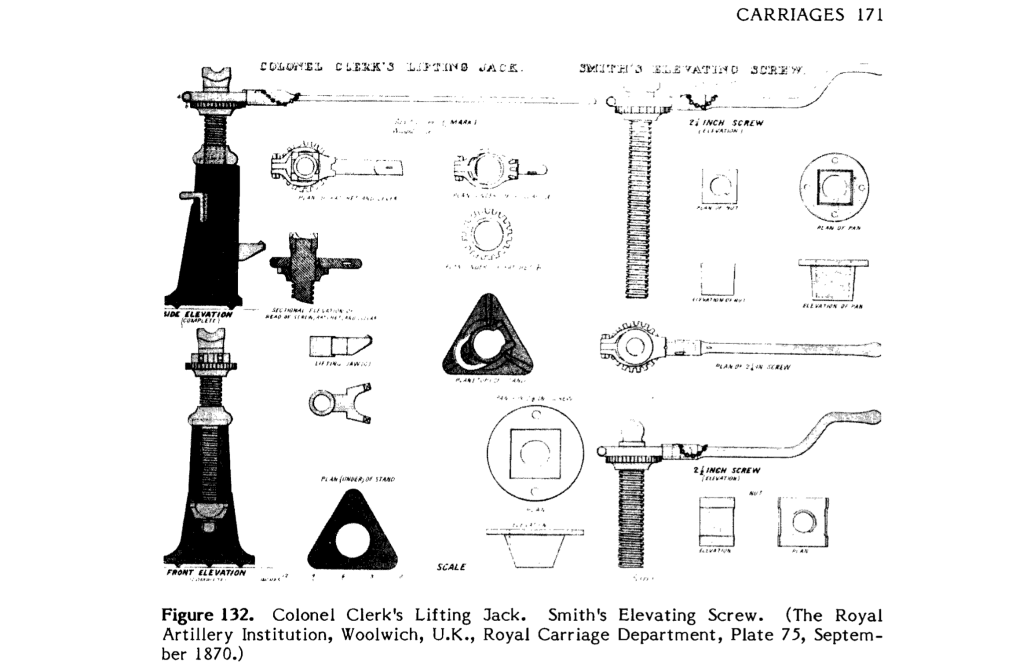

The 1861 Armstrong rifled breech loader cannon had foresights on the trunnion ring, and rear sights on the breech. The foresights had fixed lengths. The rear sights were adjustable and graduated for range. The foresights were vertical. The rear sights were canted at a 2º16″ angle to compensate for slight lateral deflection of the projectile caused by the rifling. The rear sights also had a lateral adjustment screw to compensate for movement of the target.

At 1:10 scale, the components of the sights were tiny, and I decided to not make the lateral compensating adjuster. But I did decide to incorporate the 2º angulation. That required the left and right rear sights to NOT be equidistant from the centre line of the barrel. The drilling of the barrel holes for the sight holders was consequently not straightforward, and I spent a couple of hours on the CAD drawing to work out the drilling positions, depths, angles etc. And then considerable time was spent setting up the barrel in the milling machine vise, so that the bore was horizontal, parallel with the mill table, and level when the foresights were drilled, and tilted 2º when the rear sights were drilled.

That took two full machining sessions over two days. I was not looking forward to it, knowing that a broken drill or other mishap would be catastrophic. In the event, it all worked out OK. Some pics…

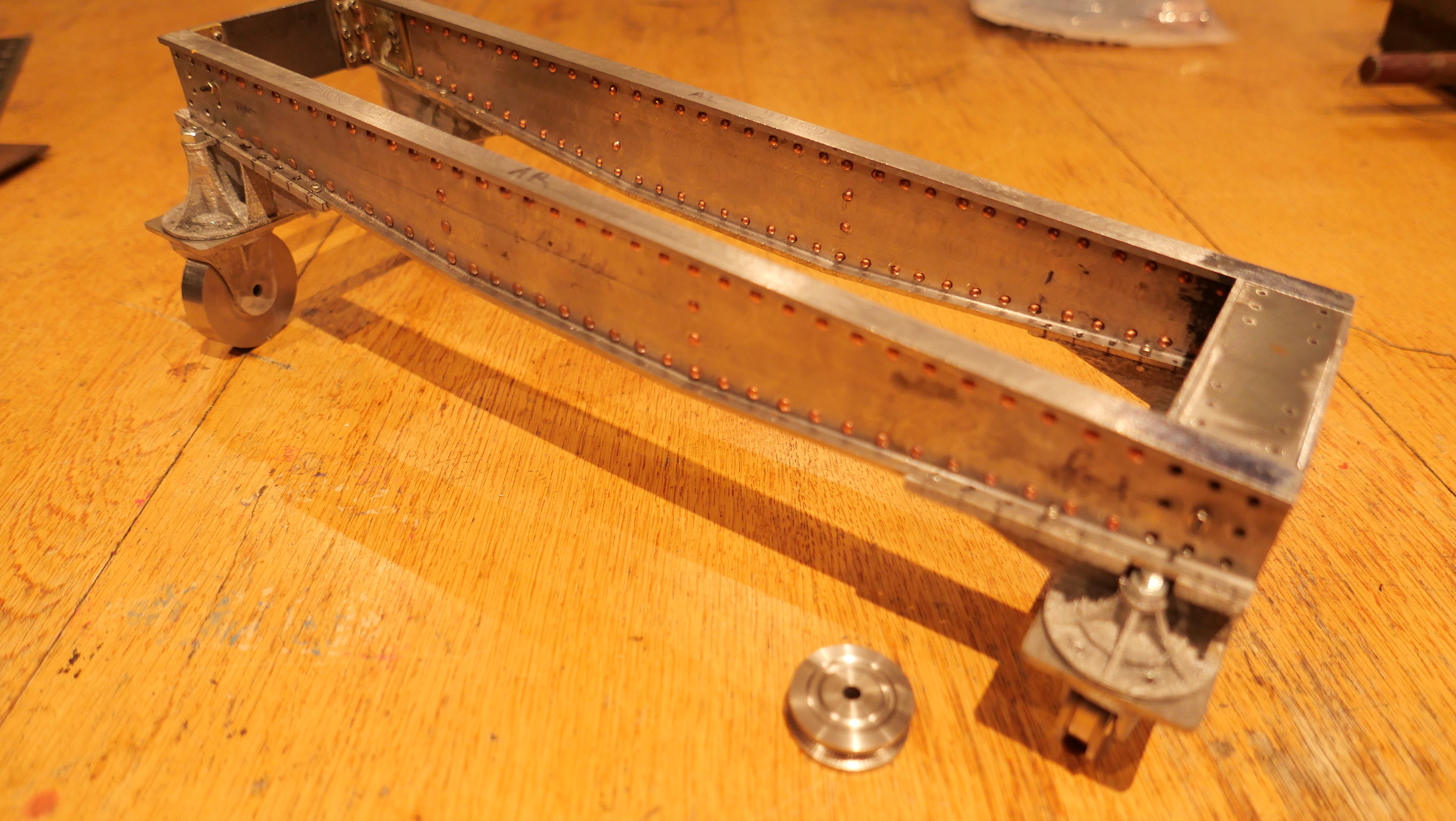

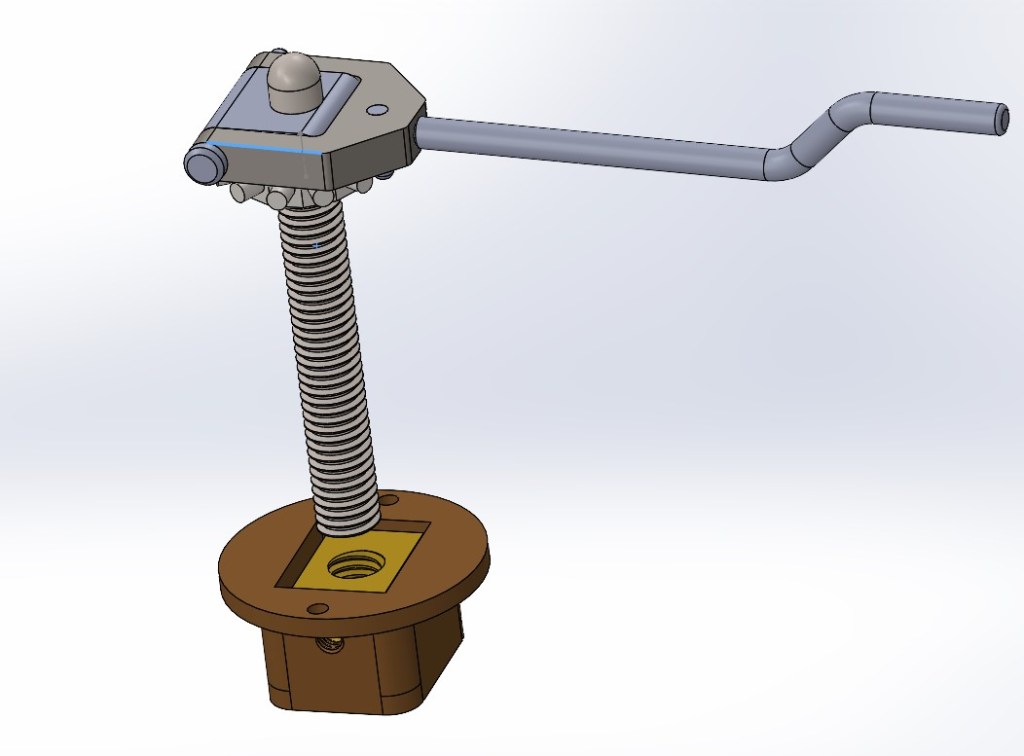

1. The 2º canting of the rear sights was established with 8mm and 10mm thick parallels sitting on 1-2-3 blocks under the trunnions. There is an 18mm rod in the bore, sitting on the jack to hold the barrel horizontal. A 4mm end mill is creating a flat surface from which to start the drilling.

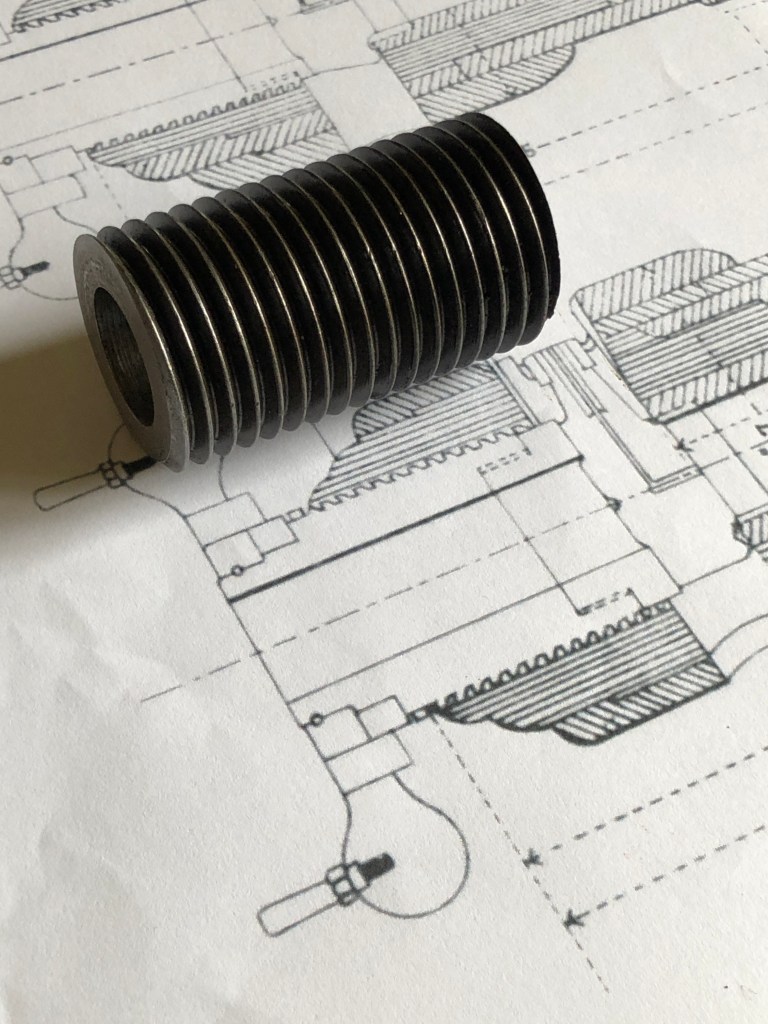

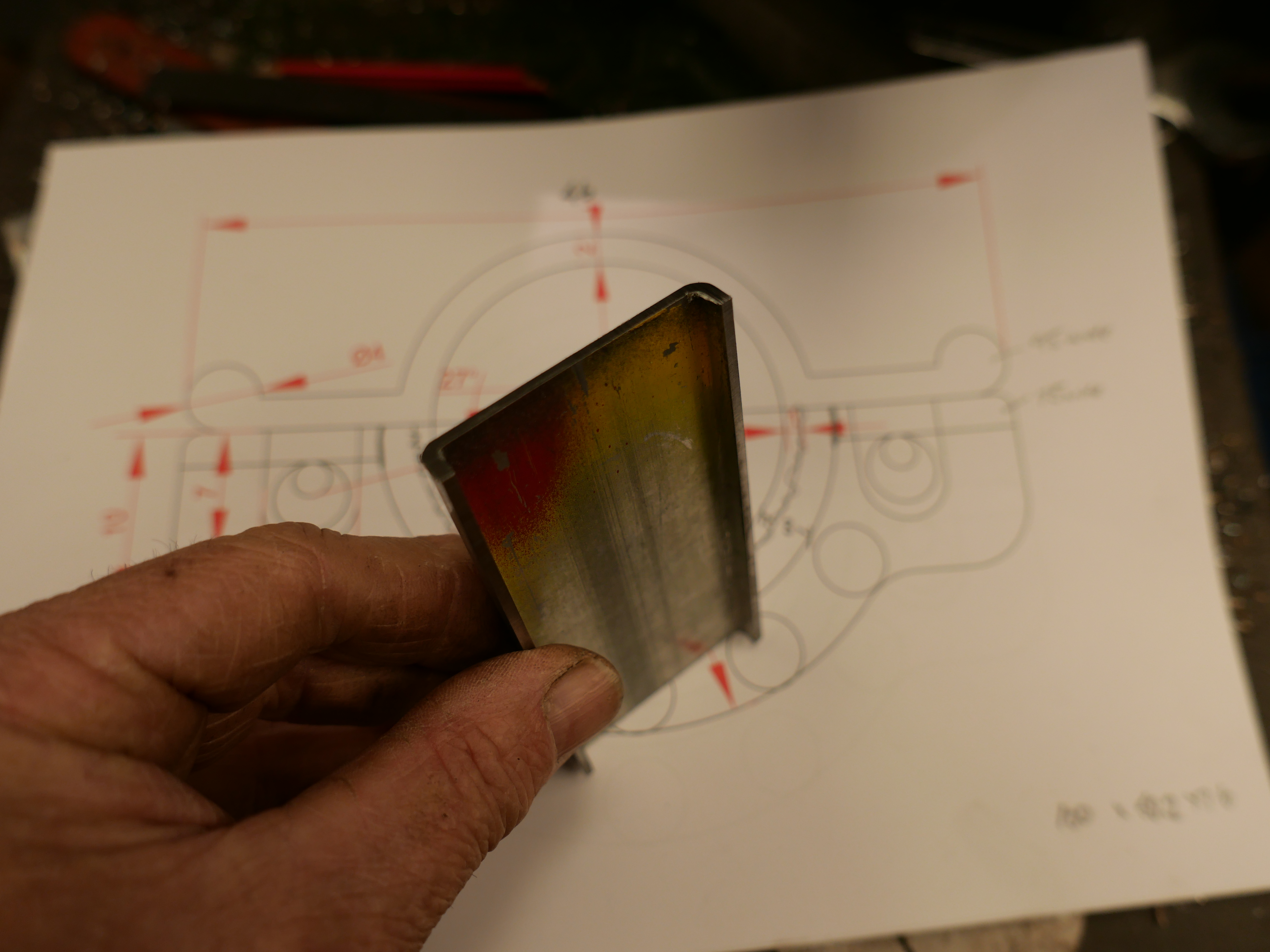

2. That is a 2mm drill bit, silver soldered to some pipe to give it some extra length. “Tension drilling” again.

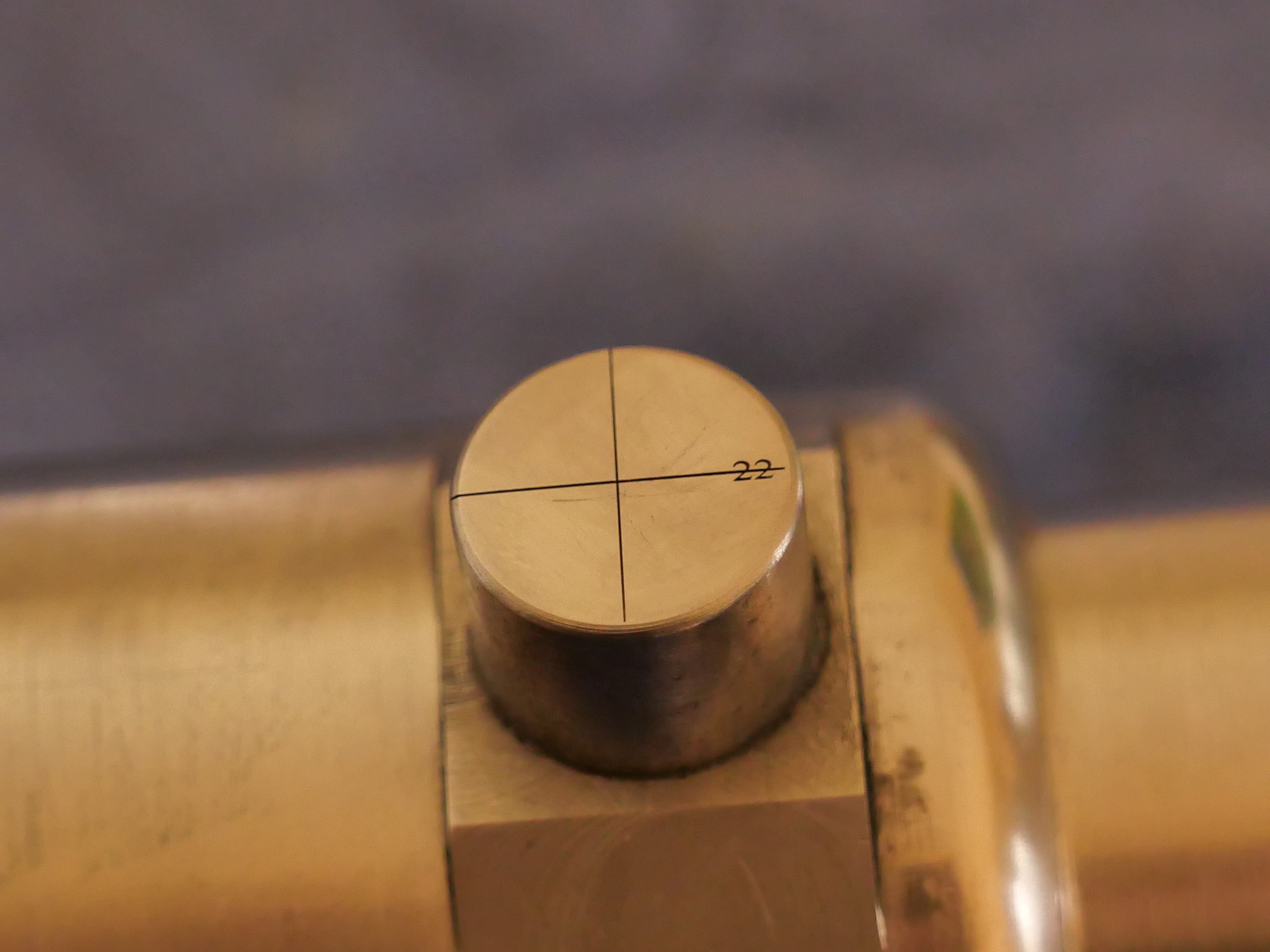

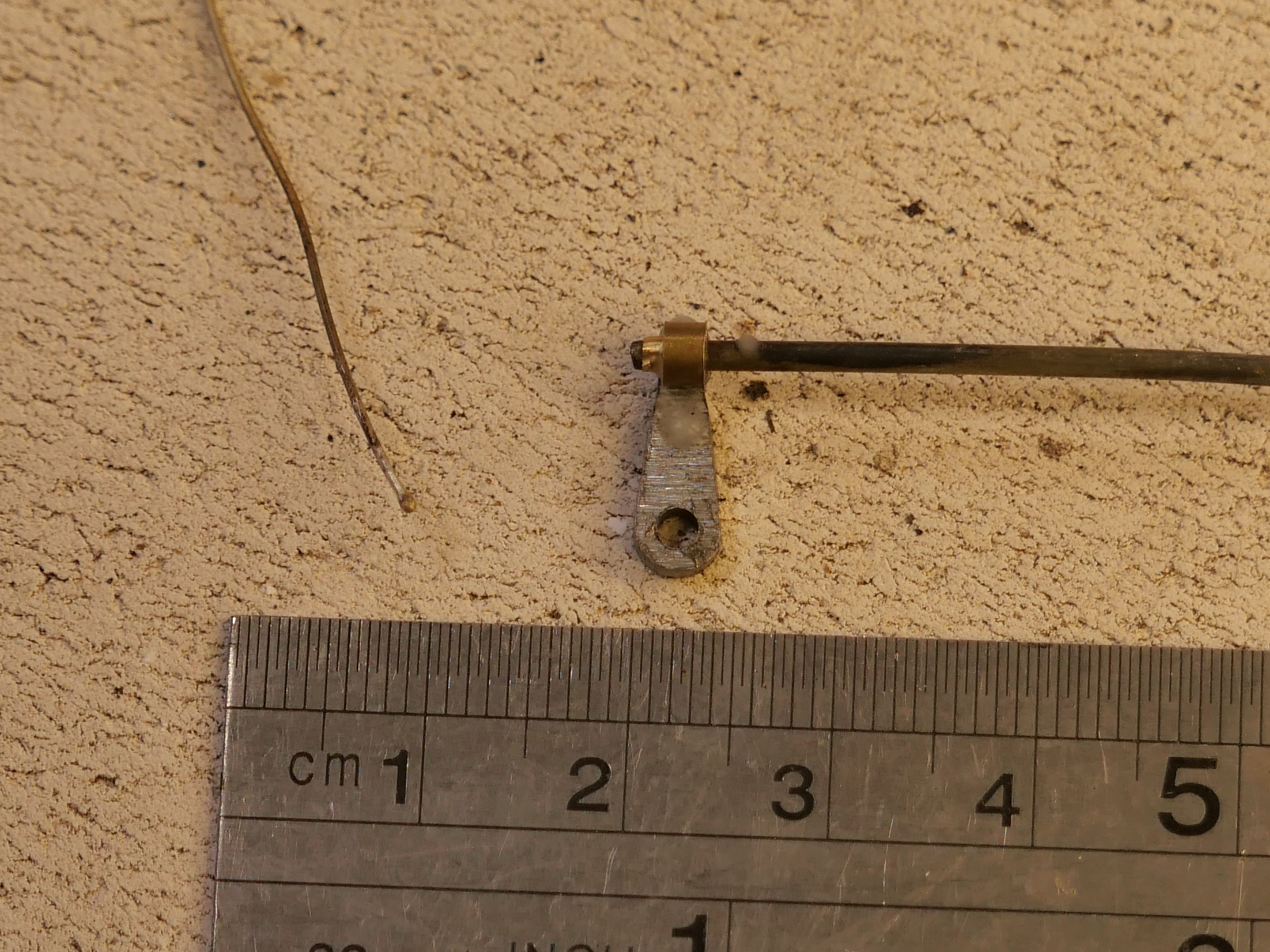

3. Checking the lengths of the foresights.

4. The almost finished sights. Left rear holder needs to be shortened. And yes, the magnified photo does reveal a previously undetected superficial crack in the left weighted arm. Luckily I have a spare part if it breaks. I must have used too much force when I pressed in the driving pins.

This series of posts is almost complete. Making the 1:10 scale model Armstrong Breech Loading, Rifled cannon, 110pr* took almost a year, and these posts were originally published by johnsmachines.com in wordpress.com. Since I am intending to cancel my subscription to WordPress I have decided to transfer some of the 900 posts to this new, for me, site.

Further old posts will gradually be transferred. And some new ones will be appearing.

Tidied the parts with a file and belt sander.

Tidied the parts with a file and belt sander.